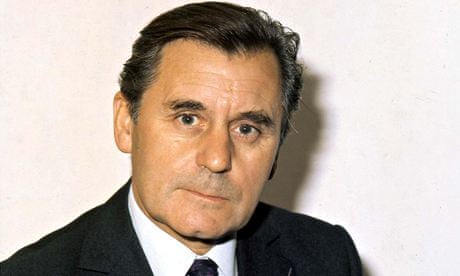

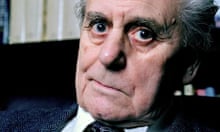

As news of academic Richard Hoggart's death emerged last week, there was a sense in obituaries and appreciations that the 95-year-old was a figure from the past, the relevance of whose work, most famously his 1957 book The Uses of Literacy, had waned over time.

My intellectual development continues to be defined by his writing, and all I can say to anyone who has yet to read his work is: do it now. We still need voices like his to articulate what is wrong, right now, with an official and media language that wilfully ignores the malign effects of class and poverty.

In his 1989 introduction to George Orwell's The Road to Wigan Pier, Hoggart wrote: "Class distinctions do not die; they merely learn new ways of expressing themselves." This is as true now as it was 25 years ago, and 25 years before that. "Each decade," he continued, "we shiftily declare we have buried class; each decade the coffin stays empty." Compare this with "We're all middle class now" (except we're not); or "Playing by the rules" (which are made by, and change at the whims of, the most privileged); or "We're all in this together" (unless you're a scrounger).

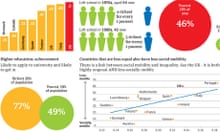

His most powerful writing is about the effect on individuals of undertaking social mobility in a society that only lets people up the ladder a few at a time, which applauds them as exemplars and then leaves them to get on with making sense of a life with working-class roots in a middle-class milieu.

Hoggart wrote in a 1966 essay of having suffered a nervous breakdown from overwork and social anxiety as he struggled towards a place at Leeds University in his late teens. The same thing happened to me two generations later and there will be others now, 20 years on, straining to pass the A-levels their better-placed classmates will sail through and wondering how much they will have to change in order to survive. Without those "anxious and uprooted" voices, to use Hoggart's words, the sharp end of class as it's lived goes undocumented.

Hoggart came to prominence at a time when a number of socially mobile writers and academics were able to take advantage of changes in society to give voice to their ideas. It was precisely because he was a social interloper that he was able to forge a new discipline – contemporary cultural studies – based on the need for individuals to look more closely at the information we consume and create, and to understand what it reveals about social relations.

We need Hoggart now because we have a deceptively flattened media and cultural landscape in which everyone is meant to take a bit, and like a bit, of everything. Twitter and Instagram give the impression of everyone having an equal voice, from the out-of-work plasterer to the millionaire art dealer. A grounding in Hoggart's work blasts through that. He reminds us that access to culture widens and narrows according to who's got the keys – and that is always the people with education, contacts and confidence.

What we can also take from Hoggart's writing is a combined defence of working-class people's agency and the fact of their individuality, which can include – uncomfortably for those on the left who prefer to treat working-class identity as a bloc-like thing forever condemned to "demonisation" or invisibility – a streak of individualism.

The need for individuals to make their own lives and to feel they are doing so doesn't have to exclude an awareness of the context in which they're doing it. You can be both of your class and your own person, Hoggart said – a belief that tells us much about who we are and what we lose in our current state of denial.