In Defense of Spoilers

Psychologists have found that people like stories more after they've been "spoiled." Why?

Last October, one week after the Breaking Bad series finale, I was having breakfast with a friend in Chicago. "Do not tell me the end of the Breaking Bad," he said. "I just started Season 2 and I have been off the Internet for the last few days. Total blackout. I've stopped following the news just to stay away from spoilers. Do not say a word."

"It was a great episode," I said.

"No, not another word," he responded. "Seriously."

Forty-five minutes later, after coffee and pancakes, I glanced at my phone and starting giggling at the table. "What is it," he said.

"This is hilarious," I responded, showing him the screen. "Somebody made a fake obituary for Walter White in the Albuquerque newspaper! How clever!"

Innocently, as if no significant information had been shared, I slipped my phone in my pocket, and looked up from the table, where I realized my grave error. My friend's face was blend of shock, confusion, loss, betrayal, and fury. "Derek," he said with a quiet intensity. As you might imagine, the rest of the sentence got considerably louder and was comprised of mostly unprintable words and a bit of table-smacking. The overall theme was that I would be paying for breakfast.

So, spoiler alert, Walter White is dead. Or, almost dead. It doesn't really matter. If you are reluctantly learning this now, in the 7th paragraph of a story called "In Defense of Spoilers," I have no sympathy for you. I do have some sympathy for my Chicago friend, a relationship I nearly obliterated over a parody obituary. But as New York's Adam Sternbergh explains, maybe I shouldn't be so hard on myself. Today's consumers are too infatuated with "the shackles of spoilers," he writes. In his words:

I love a good twist (sort of) as much as the next person, but I also understand how waiting for the big reveal distracts me from everything passing before my eyes and ears right now. I don’t think Citizen Kane — to use a shopworn example — is a lesser experience if [SPOILER ALERT!] you already know that Rosebud is a sled. In fact, the sled has nothing to do with what makes the movie great. Or, put another way, the single greatest cinematic spoiler-maestro of our lifetime is M. Night Shyamalan, and he rode his weird addiction to big reveals right into artistic ruin.

Anticipation is certainly one of the pleasures fine films and TV can offer us, but it’s not the only one, and frankly, it’s probably the cheapest. The thrill of a good twist is like artistic flash paper: It excites for a moment but offers little lasting wonder. If you’ve ever seen a good film with a big reveal, you probably immediately had the urge to watch the whole thing again — and, in my experience, the second viewing is always more satisfying than the first. Because you notice all the things you missed while you were busy waiting for the twist.

If Sternbergh doesn't persuade you that story spoilers don't spoil stories, consider the research paper published in Psychological Science in 2011, compelling titled: "Story Spoilers Don't Spoil Stories."

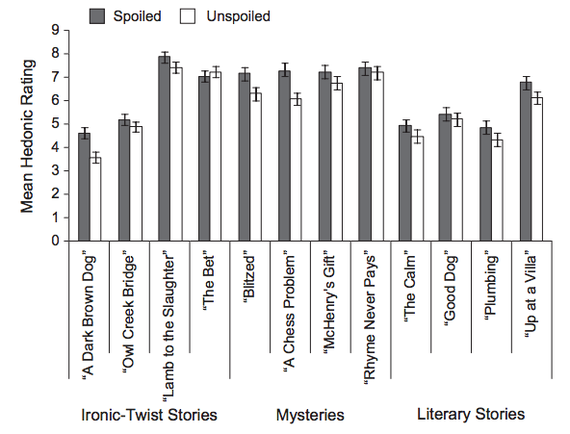

Scientists asked 900 college students from the University of California, San Diego, to read mysteries and other short stories by writers like John Updike, Roald Dahl, Agatha Christie, and Raymond Carver. Each student got three stories, some with "spoiler paragraphs" revealing the twist, and some without any spoilers. Finally, the students rated their stories on a 10-point scale.

"Subjects significantly preferred spoiled over unspoiled stories in the case of both the ironic-twist stories and the mysteries," the researchers concluded.

All Spoilers, Please!

It's one thing to say that spoilers don't ruin all stories. But how does giving away the ending make us enjoy mysteries even more?

One theory is that our anticipation of surprises actually takes away from our appreciation for the 99 percent of the movie that isn't a monster twist. "The second viewing is always more satisfying than the first," Sternbergh said, "because you notice all the things you missed while you were busy waiting for the twist." Psychologists have observed that when we consume movies and songs for a second (or third, or hundredth time), the stories become easier to process, and we associate this ease of processing with aesthetic pleasure.

A second theory from the paper is that audiences enjoy predictability much more than we like to admit. As the famous screenwriting how-to manual Save the Cat explains, most successful movies fit into highly conventional formulas (e.g.: superhero movies, love stories) where just about every person in the movie theater could probably guess the ending before the credits begin. For example, despite all the danger faced by Chris Pratt's character in Guardians of the Galaxy, if you polled audiences before the movie, approximately 100 percent of them would predict he survives the film. Giving away the ending (he doesn't die, by the way) does little to detract from the film's many pleasures.

To be fair, neither of these theories quite justify spoiling movies like The Usual Suspects, where the twist defines the movie and immediately recasts the former two hours for a first-time viewer. The defense "it's okay, you'll still really appreciate Stephen Baldwin's performance" doesn't quite hold up.

But the vast majority of written and filmed entertainment is not an elaborate act of magic whose essence hinges on the final reveal. Instead, most great stories are like Oedipus Rex, Hamlet, Star Wars, and Annie Hall—stories with endings that live within the bounds of predictability and which have been re-staged, re-released, and re-watched a million times since the entire world knew how they ended. Some spoilers are unforgivable. But most of the time, maybe we shouldn't spend so much energy at the beginning worrying about the end.