The Scary, Misunderstood Power of a 'Teen Mom' Star's Album

Farrah Abraham bizarre, abrasive My Teenage Dream Ended, has been called one of the worst works of pop music ever. But listen to it as a piece of art, and a compelling story emerges. Seriously.

In "Food with Farrah 'Inspire & Admire,'" amateur cooking-show personality Farrah demonstrates how to make something she calls a "mobile salad"—a concoction of parmesan, yellow onions, mozzarella, cherry tomatoes, chick peas, Florida avocado, and some bok choi and white asparagus sautéed by hand, all crammed into a hollowed-out artichoke and drizzled with fig tahini dressing.

At one point in the video, she admires the large Florida avocado. Cheerfully, she tells the camera: "I myself have never tried this before, so it could be a new experience for you as well!"

Farrah is a restless YouTuber; the rest of her channel is a trip through various media efforts, some self-made and others professionally produced and edited. There are home movies of Farrah and her baby daughter Sophia at home, but also a number of web shows in cooking, fashion advice, sex ed, exercise, and video blogging. Farrah off-handedly compares each of her hair wands to the sex toys they resemble and gives a lengthy shout-out to Stan Lee in the introduction to unrelated seven-minute home movie of Sophia riding a horse. She's unpredictable and charming.

But there are three videos on her channel that, even given the diversity, seem strangely out of place.

"Finally Getting Up from Rock Bottom" is one unbroken shot of colorful flashing lights in a dance club, recorded on a cell phone. The soundtrack sounds like pop music; it has the hard four-on-the-floor throb of contemporary dance-pop by Rihanna, LMFAO, and Pitbull. But then Abraham's voice crashes the party. She's speak-singing through an oppressive Autotune filter, a tool usually associated with subtle vocal tweaking for off-key performances. Here it completely deranges her voice beyond recognition—even beyond the signature distortion of rapper T-Pain, or Lil' Wayne on his rock album Rebirth. Farrah shouts semi-rhythmically, her voice forced unnaturally into a near-enough key. Most of the lyrics are incoherent. What does come through is provocative: "I came dressed up on the way down."

"The Sunshine State" is a series of shots of aquatic wildlife filmed with an underwater camera. Again the vocals are unnerving. Abraham introduces herself matter-of-factly: "FLA are my initials. Appeal to me." Then comes a rush of barely-discernible phrases: "top down, fierce cars, short skirts, high heels, makes men go loco..." At the end of the song, the abrasive dance beat cuts out, revealing the quiet recording of "Aloha 'Oe" that's been playing in the background.

The strangest of the bunch is "On My Own." The video is a series of arty home-movie shots of Farrah and Sophia playing in a park. The song is built on a synth line while a skittering breakbeat flutters in and out. Lyrics are easier to decipher, a combination of childish poetry ("My heart just stares") and measured introspection ("I wanna blame you. But isn't that so easy to do?"). About halfway through the video we realize that what seemed to be a public park is actually a graveyard.

What you wouldn't necessarily know just from watching most of these videos is that Farrah Abraham, now 21, was featured in an episode of the MTV reality show 16 and Pregnant in 2009 and starred in its follow-up series Teen Mom. Her 16 and Pregnant episode documented a fraught relationship with her parents and her on-again/off-again boyfriend, Derek Underwood, Sophia's father.

By the time 16 and Pregnant aired, Underwood had died in a car accident (the graveyard in the "On My Own" video is where he's buried). As she continued to appear as a cast member in Pregnant sequel show Teen Mom, Abraham became a genuine tabloid fixture. In 2010, her mother Debra Danielson was briefly arrested for alleged domestic assault. Abraham later revealed that throughout Teen Mom she struggled with postpartum depression and thought frequently of committing suicide (She told InTouch, "I figured I'd drown myself in the bathtub—that seemed like the easiest way to go").

Many of these developments are detailed in My Teenage Dream Ended, a tell-all autobiography released in August that reveals Abraham's tumultuous experiences between circa 2008 and present. The autobiography was a conventional move for a reality star—it's currently on the New York Times e-book non-fiction bestseller list. Less conventional, though, was a "soundtrack" she bundled with electronic copies of the book, an effort, she explains, to reach readers who might connect to her story emotionally through music rather than by reading. She told entertainment site Ology:

Most people don't look at ["Rock Bottom"] as therapeutic. To me, that was therapeutic. It was also another way for me to express myself. I'm an artist, I'm an entrepreneur. I love to dive in and experience new things now in a positive way. I have to say that they've only heard one song, but then they haven't heard all of the songs that go with the book. It is a book track. It is not like a Kanye West soundtrack or an album.

The soundtrack's 10 songs correspond to specific chapters in the book, but you'd be hard pressed to make direct connections—a skim of the book confirms that the lyrics aren't drawn from the text. Gossip sites presented the songs without much commentary, allowing commenters to do the work of howling at them. Most publications reviewed Abraham's songs as failed pop, with near-unanimous references to Rebecca Black's viral hit "Friday" from 2011. The general consensus was that Abraham's songs were much worse.

You don't need to trawl through comment threads to discover the average tone of critiques. At Popdust, Emily Exton joked that "the Internet police are trying to stop this thing from spreading, as much as contraceptives wish they could have protected Farrah's genes from doing the same." At Jezebel, Tracie Egan Morrissey mocked Abraham's accounts of her postpartum depression: "It's a song about recovering from suicidal thoughts. The irony is that it will make you want to kill yourself."

It's tempting to consider My Teenage Dream Ended alongside other reality TV star vanity albums, like Paris Hilton's excellent (and unfairly derided) dance-pop album Paris from 2006 or projects by Heidi Montag, Brooke Hogan, and Kim Kardashian that range from uneven to inept.

But the album also begs comparisons to a different set of niche celebrities—"outsider" artists.

On the I Love Music message board, music obsessives imagined the album as outsider art in the mold of cult favorite Jandek or indie press darling Ariel Pink. Other curious listeners noted similarities to briefly trendy "witch house" music, a self-consciously lo-fi subgenre of electronic dance music. In the Village Voice, music editor Maura Johnston compared Abraham to witch-house group Salem: "If ['Rock Bottom'] had been serviced to certain music outlets under a different artist name and by a particularly influential publicist, you'd probably be reading bland praise of its 'electro influences' right now."

Phil Freeman wrote about the album as a "brilliantly baffling and alienating" experimental work in his io9 review. Freeman hedged his references to Peaches, Laurie Anderson, and Le Tigre with a disclaimer that his loftiest claim was sarcastic: "Abraham has taken a form—the therapeutic/confessional pop song-seemingly inextricably bound by cliché and, through the imaginative use of technology, broken it free and dragged it into the future."

But if My Teenage Dream Ended is in fact a product of art therapy, then his sarcasm might actually be an apt description of the album.

MORE ON MUSIC

Like many outsider artists before her, Farrah Abraham's music raises questions about expectations, intended audiences, and motivations of the artist. Did she mean for it to sound like this? Should I even be listening to it? Is it supposed to be pop? Daniel Johnston famously copied Beatles chord patterns on his piano and retooled them into songs about superheroes, unrequited crushes, and depression, which he circulated on homemade cassettes. In the '90s, popular artists allied and collaborated with Johnston, highlighting the pop savvy behind his songwriting.

That possibility is unlikely here; it's hard to imagine anyone successfully covering Farrah Abraham's originals. Like Johnston, Abraham uses a popular idiom—in her case, dance music like house, dubstep, and EDM—as a backdrop for weird, free-associative expression. But unlike Johnston's work, it is nearly impossible to sing along. That would also seem to make the music parody-proof. What would be the point?

As for motivation, the Voice review positions Abraham's work as "trollgaze"—music whose primary goal is to incite galvanizing reactions in jaded, internet-savvy audiences. But that doesn't seem quite right. My Teenage Dream Ended is galvanizing, but there's a consistent earnestness in it, too. Humor, when it enters, feels insular and inscrutable, like references to Soulja Boy ("Yahhhh trick!") and a pun about "setting the tone" accompanied by the sound of a phone dialing. Meaning seems obviously there but also impenetrable; like much experimental work, it establishes rules to be learned as you experience it.

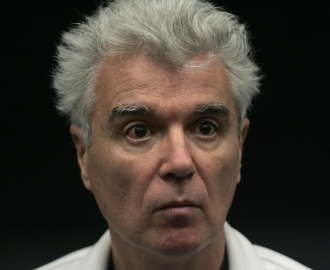

The album is dense, perplexing, and uncomfortable. It suggests everyday teen anxieties and traumas in an uncanny language that's both mesmerizing and at turns horrifying. In that sense, it's reminiscent of David Lynch's film work. Perhaps My Teenage Dream Ended is to teen angst what Eraserhead was to domestic angst. Like Eraserhead, we only get flashes of realism to ground us in a recognizable world before descending into the stuff of nightmares. Abraham's description of the new pregnancy is distinctively Lynchian: "This bump doesn't go away. Neither does the fear on my face."

Some songs are almost illegible, but nonetheless striking. In "With Out This Ring..." a few words emerge from the drone of a slow beat driven by funereal piano line: "Tell me why we're 16 and broken up? Complicated high school drama." Other bits are easily misheard: "It's a green finger—count me out!" Wait, what? But like many songs here it blindsides with one wonderful line: "I don't wanna make mistakes. I still need to make more mistakes."

In "After Prom," a warped voice chatters over a minimal house beat punctuated with stock camera flash sound effects: "Life, life, the best party you live! Laugh, don't think about the choices you choose! One o'clock and all that comes with it! So happy, ready for it!" And then comes a chorus of sorts, Abraham's hushed voice, now clear, urges, "Shh! Don't tell! Don't let it get out!" The track alternates between eerie calm and clatter, the anticipation of something big and probably bad on the way. It's a pretty good approximation of what "after prom" feels like.

There are recurring motifs and themes—games of plucking flowers ("he loves me, he loves me not"; "we're fighting, we're fighting not"), relationships that are never really "on" or "off," parents meddling at the periphery. There are lots of asides that might be absurd or profound, depending on whether or not you heard them correctly: "our bodies will hold us together." The production is passable, exactly as competent as needed to scan as music so that Abraham can try things out in the foreground.

Eventually all of the bits and pieces, the noises and melodies, the snatches of poetry and word salad, start to harden into a story. Girl loves boy she doesn't really like. Girl gets pregnant. Boy dies. Is she distraught or relieved? From "Searching for Closure": "I love you. We're finally at peace. No one will get between us any more." (Maybe he was the one getting between them.) Girl gets angry. Girl moves on, maybe (to California?), maybe not. "I can only put so much in a song," she admits from the start.

The broad strokes don't seem that far removed from Abraham's autobiography, but as usual, limiting the impact of music to the autobiographical details of its maker deadens it. It's art, after all, and it belongs to the world now, for better or worse. But why does it seem inconceivable that a former reality show star might also be a young artist following inchoate creative inspiration to strange places? Not being successful at something it isn't trying to do shouldn't damn any work. It only damns those who refuse to believe good art can come from anywhere and for any reason.

You can't really blame a critic for forcing the link to mainstream pop music, which is usually a safer place for people to ostracize rather than own up to things they simply don't know what to do with. Rather than accepting ambiguity and confusion, listeners short-circuit an important part of analysis, where along with figuring out whether something is good or bad, you also try to make sense of what it actually is. It seems obvious that Abraham's music is operating outside of lots of pop conventions, but very little reception of the music so far has grappled with what's really there, the lovely, maddening mess of it all. What is it?

Who knows—or, in the end, cares—about what it was supposed to be? Maybe it wasn't supposed to be anything in particular. Maybe the process was just like the "mobile salad," an impulsive, eccentric expression crammed into an unexpected shell (and, like the cooking show, probably given a mild professional gloss from a few unnamed producers). "I just was playing around with music," Abraham told MTV, "and people took it WAY too serious."

The playing around is clear. But as a dark and compelling experiment in abstracting and compressing the vicissitudes of "high school drama" into a little under a half an hour, My Teenage Dream Ended is also worth taking seriously.