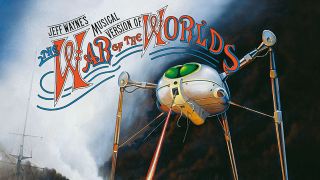

When Jeff Wayne came to compose the score for his musical adaptation of HG Wells’ pioneering sci-fi novel The War Of The Worlds, he approached it in a style similar to that giant of British fiction. Devised in the order the album plays, Wayne deliberately created the album as a series of episodes – the same way as the book was originally written: as an episodic story for a regular magazine with cliffhangers at the end of each part to lure readers back for the next instalment.

“HG Wells had to discipline himself by writing each chapter,” says Wayne. “So I followed his lead – and a large percentage of the track titles are names of chapters in the book.”

Such working practices were symptomatic of Wayne’s dedication to a worthy musical adaptation and his grand vision of what has since become a record-breaking album. Spanning 95 minutes, it has now sold 15 million copies worldwide. It was re-released in 2005 with little fanfare but ended up at Number 7 in the album chart, rediscovered by yet another generation. Another reissue this year shortly after the 30th anniversary of the original 1978 release – with new material culled from the recent live tour – proves its popularity is as strong as ever.

Jeff Wayne originally discovered The War Of The Worlds as a kid after reading HG Wells’ The Time Machine and seeing the 1953 movie version of TWOTW. His subsequent interest in adapting it into a musical work was piqued by the story’s analogous social comment. “HG Wells was taking a pop at the expanding British Empire,” says Wayne. “He created these Martians with tentacles as an analogy for Britain’s tentacles of power and the misuse of power. He had a social comment and a good vision of the world and that appealed to me.”

Wayne accounts for the album’s success because of its ability to defy any single form of music. Its genre-spanning appeal is down to Wayne’s unique approach to the score.

“I had a clear idea of wanting to ‘tell’ the score through the unfolding of the story,” he explains. “So through the eyes of humanity, the symphonic strings and acoustic sounds would prevail. When it was being told through the eyes of the Martians, it was highly electronic and aggressive.”

It sounds simple, but the complex structure of Wells’ narrative proved testing even for a classically-trained composer (originally a journalism graduate, Jeff opted for music instead then studied at Trinity College Of Music in London) of Wayne’s calibre. “The hardest composition was trying to interpret HG Wells’ vegetation of death, The Red Weed. It’s described as both deadly and beautiful – both in the way it looks and the way it moves. So I composed a theme that was in two keys; what I wanted was a beautiful melody, and a beautiful dissonance. Not a bad dissonance like scraping your fingernails down a blackboard, but something that gave it an underlying theme of beauty, but ominous too.”

Wayne’s scheme paid off. The Red Weed’s evocative soundscape of post-Martian invasion England is one of the most atmospheric parts of the album – underlined by the anecdotes Wayne has since received about the piece. It transpires that even foetuses in utero stop kicking about and pay attention when their mothers-to-be play it.

“Through the years I’ve had tons of letters from pregnant mothers who’ve listened to The Red Weed because they find it very calming,” laughs Wayne. “They say, ‘the rest is rubbish but The Red Weed helped me through my pregnancy!’”

His approach to his epic composition clearly has more common with a composer/arranger/conductor/producer rather than the mere songwriting pop musicians of the 70s. Nonetheless, he does admit to being influenced by the prog bands of that decade – especially Pink Floyd who used sound-designed effects, such as those on Echoes. It’s a similar method to how Wayne scored sound effects on TWOTW, using prior knowledge of cutting-edge technology of the era.

“I had one of the very first Moogs in 1968,” says Wayne. “Electronic scoring and all that gear was always in my nature. Robert Moog came over to install it. You had to program it and it was very prehistoric by comparison to today. So when I started TWOTW, I was in familiar territory.”

Although he doesn’t personally consider TWOTW a prog work, by the time Wayne came to record it, he was no stranger to the genre. He’d previously worked with Rick Wakeman and the mighty Emerson, Lake & Palmer were even recording at in the same studios, central London’s Advision, where TWOTW was laid down (“I was forever bumping into them making cups of tea”). Advision was popular with 70s prog bands for its large capacity. Wayne’s scores were so long that some of his musicians would have them displayed on up to 10 music stands that snaked around them, in order to read all the music alongside the script.

The album spawned two hugely successful singles, both featuring Moody Blues frontman Justin Hayward on vocals: the mournful ballad Forever Autumn and the epic album opener The Eve Of War. The latter’s phenomenal ongoing popularity is testament to the track’s enduring bombast. A dancefloor favourite in the burgeoning disco scene of the late 70s, it’s been remixed and sampled countless times from then, to the rave culture of the late 80s and beyond.

Its longevity is especially rewarding for Wayne who, even now, enjoys discovering new forms of making music. And his offspring is carrying on that family tradition: “I have a son called Zeb who’s a top DJ in one of the main clubs in London,” says Wayne. “I’m always hearing him working on things in my studio and I find that really invigorating – there’s some fantastic writing and production techniques in that world.”

Despite Wayne’s prog rock influences, at the time of its recording, a much more immediate – and surprising – influence helped shape the attitude of TWOTW.

“When I was composing TWOTW, it was the height of the punk revolution,” says Wayne. “I was living as a young musician in that world. In fact I think of myself as part of that group; as having as much spirit – angst – as the punk musicians: I had something I really wanted to say and say it the only way I knew how to, and that’s what came out of me with TWOTW. It was nothing more complicated than that.”

Despite featuring some the best musician talent of the 70s, TWOTW boasted many coups for its performer roster – not least Welsh actor Richard Burton’s pitch-perfect narration as the journalist, Phil Lynott’s insane Parson Nathaniel and David Essex’s naïve Artilleryman.

In an attempt to snag Burton – Number One on Wayne’s ideal cast list – Jeff took a long shot and sent a script to Burton’s stage door whilst the actor was appearing in a New York production of Equus. Wayne enclosed a long letter outlining his vision and why he thought Burton would be perfect for it. He then thought nothing more of it.

Just three days later, Burton’s manager of the time, Robert Lance, posted a call to Jeff. “Richard loves the whole idea, loves the script, count him in, dear boy,” he told a shellshocked Jeff.

“It was probably the easiest and most fluid part of the project,” reflects Wayne, “although Burton was this huge international name. He had this reputation as a hellraiser – in terms of drinking and marriages. But he was the most charming, prepared and professional man you could imagine.”

The album also features another tour de force by someone else who you wouldn’t normally associate with prog: hard-drinking and hard-living Thin Lizzy frontman Phil Lynott. At the time of the recording, Lizzy were riding high on the success of their career-peaking Jailbreak album. But Lynott himself had reservations about taking part, because of his lack of acting experience. Jeff quickly allayed his fears. “I told him that that the intro to Thin Lizzy’s Fool’s Gold (from Johnny the Fox) was very dramatic.”

As Parson Nathaniel, Lynott sings the mini-opera and album highlight The Spirit Of Man alongside Julie Covington.

“He was brilliant to work with and it’s tough on Phil that we’ve started doing it live,” says Wayne. “Instead of trying to emulate Phil – because I don’t think you can; he had a different, soulful style of singing that was unique to him – we’re trying to get artists to interpret the role and make it their own. But it was a privilege to work with him.”

Before TWOTW, Wayne had worked with David Essex as his producer and arranger and toured as his musical director. Julie Covington appeared with Essex in a 1960s production of Godspell and Wayne got to know the cast while dating an understudy. Eventually he formed a band with both Essex and Covington and they performed as The Godspells along with Marti Webb, doing gigs around London.

From the day Wayne signed the contract to acquire the rights for the release in January 1975 – which he considers as the beginning of the project – until the album’s original release in June 1978, the whole project took just under three years. No mean feat considering its length.

“It was a beast to harness,” says Wayne. “But it was a very spirited production. Everyone thought I was bonkers for taking it on. Two-thirds of the funding came from my life savings. The artists were very positive about trying to use their skills in helping me along – that ran through the whole three years of making the record. I look back on that as one of the most enjoyable periods creatively in my life.”

Even so, such a mammoth project would obviously have its pitfalls. Bizarrely, the biggest setback occurred after the album was actually finished.

“Having spent all that time writing, producing it and finishing mixing it, we celebrated with some champagne,” recalls Wayne. “The next morning I had a call from the studio manager. He said, ‘Are you sitting down?’ He told me the tape operator had accidentally slashed through side four, thinking it was an out-takes reel. It was in pieces and on its way to a dump with the rest of the trash. I thought it was a bit funny. We spent another week in the studio and it was a probably a better mix than the original.”

So there’s a rare mix of the last quarter of the album that no-one will ever hear?

“Not unless they’re prepared to go the dump where side four is, in about 8,000 pieces!”

Considering the album’s ongoing popularity, perhaps we shouldn’t rule it out. So as the album that took prog music to the masses under the radar, will Wayne officially concede its prog status?

“When I was composing, arranging and producing it I never thought of a music genre,” he avers. “It was just something I wanted to say and whatever came out, came out. ”

But it’s still an album that certainly ticks all the boxes of the true definition of ‘progressive’: groundbreaking, cutting-edge and seminal.

“That’s how I would see it; you’re taking an adventure, and not necessarily doing something that’s a format,” says Wayne, and with typical understatement: “It’s had quite an unexpected life.”