It’s been ten years since New York City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene began assigning letter grades to restaurants. Today, diners focus on the grades posted in each restaurant’s window, assuming they’re objective assessments of establishments’ cleanliness. Cooks are obsessed with the points system that the Health Department used to determine violations. And restaurant owners loathe the system because the whole thing feels like a slow-motion bureaucratic shakedown whose real purpose is to be a steady, easily manipulated revenue stream for the city.

In this way, the system is perfectly constructed: No two pieces align conceptually, leaving plenty of room for error and exploitation. Yet there is no way for owners to avoid it, and they would never comment on it publicly because they are terrified of repercussions that very well might shut down their businesses. Whoever designed it may in fact be an evil genius.

I opened Bruno Pizza in the East Village in 2015. When you open a restaurant in New York City, you will, naturally, be inspected by the Health Department. Before I opened, a couple guys came to kick the tires. They looked around to make sure we had enough hand sinks close to food-preparation areas, to confirm we’d put the “employees must wash hands” signs in the restrooms, stuff like that. They asked about hours of operation, reminded me that someone with a Food Protection Certificate must be present at all times, and then cleared us to open. All in all, it was easy. But we were on their radar.

From that moment, the staff kicked into “let’s get open” mode. Once the DOH — everyone in the New York City restaurant world calls the city’s Health Department the DOH — signed off, it was time to go. So, even though we never felt “ready,” we opened. And it was crazy. Really crazy. Eighteen-hour days, no days off. A total blur. But we managed to keep it together and pushed through the first couple weeks.

Then, I noticed another layer of crazy being added to the mix. The cooks started to act extremely paranoid. They started to yell at each other about the DOH and points.

“Dumbass, if you leave that beef out, that’s points!”

“The ice machine hasn’t been cleaned — that’s automatic points!”

“Kill that fly! That’s a point!”

The health inspectors always show up unannounced, so cooks freaked out anytime someone came in wearing a backpack. They also came up with crazy schemes — special codes for the hosts to use, silent signals for cooks to alert one another — and plans that made me wonder if they were purposely trying to sabotage my business.

“If DOH walks in,” they would say, “no matter what food you are working on, throw it all in the garbage.” I’m sorry, what? The logic here was based on an inspection loophole that cooks tend to get stuck on: Food in the trash is considered trash (duh), so the inspector won’t be able to scrutinize anything you throw away.

“When the inspector gets here, go around and tell all the diners that we can’t make their food and they should just leave.” Huh? That sounds like running a restaurant in Bizarro World, but not here — not my restaurant.

No, the ingredients are too expensive to just throw away. And the pesky little detail about diners is that we need them so we can pay the bills. Instead, just be ready, and deal with it when the inspector shows up while still doing your job. My attitude was always: “Just label stuff and keep shit tight all the time and it will be fine.” But not everyone shared my “constant vigilance” mindset.

“Dude, you don’t even know how bad the DOH is,” the cooks would say. “You’ve never done this — they will shut this place down!”

It was before service on a Thursday. I remember because it was the night of Eater’s 2015 Awards party, and Bruno Pizza was being (ironically?) honored with a “So Hot Right Now” award. When I walked into the restaurant that day, I could immediately tell the energy had changed. “Health inspector,” a server said.

The guy was standing at the pizza station poking at a tray of squash on the speed rack. “Why isn’t this labeled?” he asked the frightened cook. The correct answer would have been that it just came out of the oven and the label was about to be added. But the kid just stammered. Where the hell were the head chefs? Why weren’t they with the inspector? Eventually, one showed up and we all walked downstairs together.

An intern was making pasta. Her hair was pulled back but she had no hat. Points. There were a couple of flies in a corner of the utility room. Points. A small puddle of water on the floor leftover from mopping. Points. Ice machine. Points. (It doesn’t matter how clean you think your ice machine is; my guess is that every inspector can wipe a smudge of dirt from one if they really want to.)

The dish machine also (supposedly) had a chemical level that was a little higher than it should have been — even though technicians came in all the time to make sure it was running correctly. In retrospect: bologna. A technician once told me that health inspectors will sometimes use the “wrong” testing strip on purpose to see if the restaurant’s intimidated cooks will correct them with the right one.

When it was all done, the inspector told me, “There are some issues here. Someone will have to come back.” He gave me the report with the violations and left. We’d get our letter grade after the follow-up visit.

The inspection report was laid out like a court summons, with a date when I could go and contest any of the violations, if I wanted to. An acquaintance, who was the head of compliance for a large restaurant group, told me I needed to go in hopes of reducing the fines. Fines? He gave me extensive notes and how to speak to the judge about each violation. He didn’t have to do such a nice thing, but when it comes to the DOH, restaurant people tend to look out for each other.

Using this colleague’s guidance, I took photos, wrote responses for each violation, woke up early for the prescribed morning court time, put on a suit, and went to sit before the tribunal judge and defend the restaurant. Lo and behold, the judge dismissed some of the violation points! After the hearing, I was directed to go to a window to register the results. I fed my papers to the clerk through the slot under the bulletproof plex, she scanned them, and then told me that, since we had fewer than 14 points and I was a first-time restaurateur, the fines would be waived. Amazing — or so I thought at the time. Now, I think it’s a subtle design wrinkle that gives owners a false sense of security.

The DOH said the follow-up inspection would happen in about ten days. So, of course, another inspector showed up more than two months later — in the middle of a slammed Friday evening service. It’s the kind of timing that makes every restaurant owner groan, “Whhhyyyyyyyy????” When people leave a restaurant disappointed that their food was slow, due to a health-department inspection, they never write a crap Yelp review of the health department.

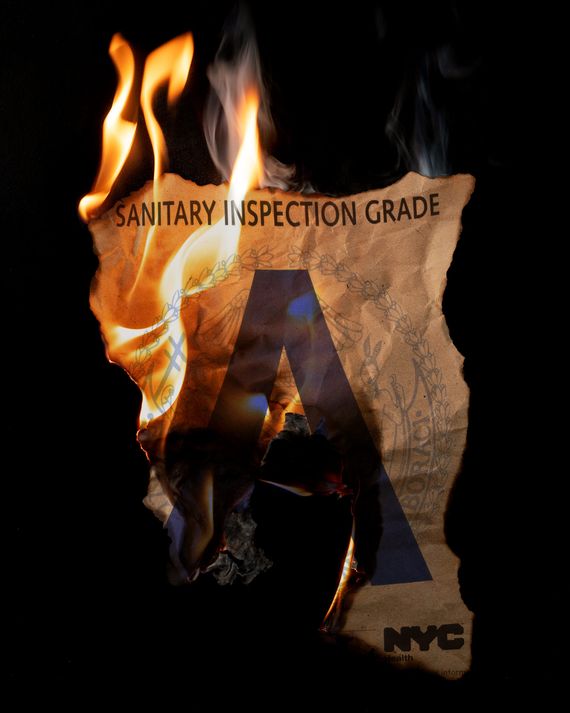

Fortunately, the inspector breezed through the restaurant. He finished, sat down, and pulled the “A” grade out of his bag. Phew! Diners who saw the whole thing unfold clapped. Cooks took selfies with the grade and posted it on their Instagrams.

I’ve seen other kitchen teams post about their A-grades, too. But I’ve never seen anyone post about the fact that it took them two separate inspections, and cost the owner $800 in fines to get that “A.” And not one cook came up to me and said, “Hey, sorry we didn’t get this ‘A’ on the first inspection.” I actually think that they are so focused on “points” that the notion of fines attached to a grade just doesn’t cross cooks’ minds.

By and large, the public assumes that inspectors go to restaurants once, give them their grades, and leave. But as I would come to realize, this “two-move” inspection play is brutally genius. It enables the DOH to get its fine money, since the first inspection can easily result in $1,000 worth of violations. The restaurant still gets to eventually display an “A,” and the public doesn’t worry about how the grades are really earned, continuing to think that this city is a bastion of pristine kitchens.

Another brilliant aspect of the grading system is that the DOH requires at least one person with a “Food Protection Certificate” to be in the restaurant at all times. Usually called a “food handler’s card,” the city asks cooks to pay $24 to go take a test at an office on the Upper West Side. If you pass, your license is good for life. (Is the city sure that, in this age of changing climates and mutating virus pandemics, food safety best-practices are not going to need an occasional update?) Yet it was also surprising to me how few cooks had food handler cards. It seemed like I was always hovering around 10 percent of my employees.

Even I didn’t have my own card for a while, which was my responsibility. But as an owner, I justified it by telling myself that I hired people to handle the food. So it was also their responsibility to make sure everything adhered to DOH rules while I focused on payroll, lawyers, bills, a nightmare landlord, wrangling wine vendors, etc. But it was this thinking that got me stuck without an employee who had the Certificate. A cook with a card quit, and shortly after that, another one just didn’t show up. We were of course due to be re-inspected by the DOH any day, but luckily, one of my investors, Mark, had a card and said he’d hang out at the restaurant until the inspector showed up. Amazing!

One night, though, as we were cleaning up after service, Mark came over and said his son was home without a babysitter, and that he needed to leave. We were done making food, so I thanked Mark and told him to go home. And, of course, as if written like a bad screenplay, the health inspector showed up five minutes after Mark left.

The inspector flashed his badge — they have badges, like cops — and asked for the food handler’s card. I handed him Mark’s.

“Is this you?”

“No,” I said. “This is the guy that manages our food handling. He just left because he didn’t have a babysitter and had to go home to watch his son. We were done making the food.”

“He should be here,” said the inspector.

“MARK! DOH!” I texted, furiously. “They’re HERE!” Mark — hallelujah — said he’d come back.

Meanwhile, the inspector was looking at the flour dust in our pasta extruder, nevermind that nothing like this is mentioned on the Food Protection test.

“You have mice,” the inspector then said, waving his flashlight under a sink.

“We don’t have mice,” I told him. “I can show you the pest-control reports.”

“I see mouse excreta.”

Excreta?

“That is a grain of wheat,” I said, picking it up. “We grind flour here.”

He ignored that, as well as the pest-control log I showed to him. He hadn’t even gotten to the ice machine when he said, “Someone’s going to have to come back.”

In the end, due to the person with the food handler’s card not being there the moment the inspector showed up, the fines listed on the report added up to $1,200. And I had to put a “Grade Pending” sign in the window. Ugh.

At my prescribed court date, the judge dismissed most of the charges, but when he got to the food handler’s card violation — and heard the babysitter explanation that I thought sounded reasonable — he gave me what seemed like a canned answer: “The rule of thumb is that whoever is unlocking the door in the morning and locking up at night should have a Food Handler’s card.” He also let the $800 fine stand. Ugh again.

It makes complete sense that someone should be certified with proper food-safety training before they oversee the food handling operation at a business that serves food to the public. But it makes less sense that the person has to be there every second the lights are on. I worked in several architecture and design firms through the years, and the bosses didn’t have to be around every second of every day for the project teams to understand the level of care and quality that was expected of a licensed architect. We didn’t all suddenly start drawing with crayons because the boss went home for the night.

So why was the Health Department different than other professionally licensed scenarios? It would, in theory, still be a violation if the entire kitchen were pristine, but nobody with the food handler’s card was present. It always struck me as simply odd, or as one more way for the city to cite restaurant owners and extract some extra cash.

Often, other violations made no sense at all, or the inspectors didn’t listen if you told them they were wrong. There was the time an inspector walked into our wood-storage room, looked at the row of wood we stacked for our pizza oven, and told me I was only allowed to store one day’s worth of wood, and that we had more than that.

“The building code says that you can store one day’s worth of wood within six indirect feet of the wood oven,” I explained, “and one week’s worth of wood in a one hour fire-rated, sprinklered room, which this is. I read the building code myself and the permit drawings were approved by the Department of Buildings.”

She didn’t want to hear it. Another fine. Another court date. This process was soul-crushing.

The only thing I could do in these situations was try to work it out with the judge. In this instance, I told her about my wood-storage conversation with the inspector, that she was wrong, that no other inspector had ever had an issue with my firewood storage, and that I felt like the inspector then went on a hunt to find additional violations after I pointed it out.

“Oh please!” was the judge’s response. “Listen, everyone that comes in here thinks they are being persecuted.” She understood my concern, she said, “but, look. Don’t go complaining publicly about it. They will come back and turn your place upside down.”

What she was describing sure sounded like a shakedown to me, by an agency that in its own estimation raked in more than $20 million worth of fines from New York City restaurant owners in a single year. For chains, and bigger restaurant groups, a few $1,000 fines each year are probably no big deal, but for small, independent restaurateurs, they can be an existential threat.

I once checked out a vacant restaurant that had recently become “available.” The situation was extremely weird: Food was still in the coolers, and alcohol was still lined up behind the bar. “I don’t know what happened,” shrugged the landlord. “The restaurant owner just closed up one night and didn’t come back. Not sure why.”

Then I saw a few sheets of paper, face-down on the bar counter. The top three sheets were a health inspector’s report, listing a bunch of violations and their associated fines. The last sheet was the “‘C” grade that the owner would be required to put in the window. A “one-two” gut punch from the city: pay once, with the fines, and pay again when customers see the “C” and get scared away. Odd because the place seemed pretty clean. Restaurants are constantly struggling to survive, but sometimes, a Health Department fine is all it takes to push the business over the edge.

A friend who has restaurant experience both in and out of New York once put it to me like this: “Other cities tell restaurateurs, ‘We’d like to help you succeed.’ New York says, ‘Give us the money.’”

One night, I was talking to one of our regulars, Sean, about the DOH and how difficult it was to find the money to pay the arbitrary fines. He owned a consulting business and had roughly the same number of employees that I did at Bruno Pizza. “I have a couple desks with a few people,” he told me. “The city never comes around to inspect anything, and I cleared more than $8 million in sales last year. How much did you make?” I frowned, and glared back at him. He just laughed. “Maybe you’re doing something wrong?”

What I really wondered is why restaurateurs do it at all. Of course we do it because we love it. But Health Department fines can make it really difficult. We all complain about it privately, so, why don’t more owners speak out publicly? My bet is that they will turn your place upside down is a terrifying prospect, and nobody wants to risk it. Heck, the only reason I can write this is that a fire in an apartment above the restaurant forced my Bruno Pizza to close in 2019. Otherwise I would be too scared of the city to say anything, too.

If the city wants to make a case that it fosters an environment that encourages small-business growth, restaurant fines don’t seem like a great way to show it. And if the DOH wants to convince owners that the restaurant grade system really is designed for the public’s safety, and is not actually a cleverly designed revenue generator, why not greatly reduce, or eliminate the fines? Why not restructure the reviews and point system so that inspectors are seen not as cops but as coaches who want to help the restaurants in their care flourish? Otherwise, it seems to me that the city’s restaurant landscape will continue to suffer as more and more restaurant owners in New York wonder if there’s a smarter way, or a better place, to conduct business.

So next time you walk by a restaurant and see that “A” hanging in the window, it’s worth thinking about what it really means. It might be looking out for public safety. But it’s also a supersmart distraction that, whether intentional or not, cleverly disguises a massive moneymaking operation hiding in plain sight — and it really is absolutely genius.