Today in Tedium: You ever notice how a phrase comes out of nowhere to sort of take over the way we perceive an issue? Maybe one day you were looking for a computer, and all of a sudden, a random certification you’ve never heard of comes to define the way that you think about that computer. You, my friend, are a victim of marketing. But marketing does have its benefits, and one type of marketing in particular played an important role in the mainstreaming of the home computer: The concentrated push for “multimedia.” This effort in the early 1990s gave computing brands something to push for, and by the time they were done, the computer industry was far larger and more prominent as a result … even if, ultimately, multimedia faded away in the end. Today’s Tedium talks about the concerted effort to sell the computing-buying public on “multimedia.” — Ernie @ Tedium

Looking for a little help in figuring out your approach to productivity? If you’re a Mac user, be sure to give Setapp a try. The service makes available hundreds of apps that can help you get more focused, simplify complex processes, even save a little time—all for one low monthly cost. Learn more at the link.

“The year after I joined, I wrote a research report observing that new technologies go through a predictable path of overenthusiasm and disillusionment before they eventually provide predictable value. … The note was called ’When to Leap on the Hype Cycle,’ and I had no idea what it would lead to. Today, Gartner creates about 100 Hype Cycles every year and the concept has made it into popular culture as well as academic literature.”

— Jackie Fenn, an analyst with the technology research firm Gartner, discussing her role in inventing the concept of the “hype cycle,” an important concept in the recent history of technology that describes the nature of broader trends to hit a wave of interest before a use case emerges. Her 1995 research paper, a modestly written document that commented on an interesting trend, came to define Gartner’s entire business as the analysis proved durable and broadly applicable. If the hype cycle existed when multimedia did, you bet that it would have had a spot on the hype cycle.

An example of a Packard Bell ad. Note that $1,169 gets you the full package. (Supercooper/Flickr)

When you bought a multimedia computer in the early ’90s, you were generally sold on a full package. Here’s why

I remember in the early ’90s looking at Best Buy circular ads and seeing these tricked-out computer packages that didn’t just promise to bring a computer into your home, but that could bring a multi-sensory experience into my home office.

It wasn’t just the beige box on its own. It was the whole package—the monitor, the speakers, the graphics, the video, the music, and the interactivity. It was encyclopedias! It was Myst! It was the Packard Bell ideal, and one that moved a lot of units in the early-to-mid ’90s.

And the moving of those units? That was no accident. It was a part of a broader movement to bring computers into the home in a big way through an industry-defined standard that came to define modern computing. In the fall of 1991, the Software Publishers Association created the Multimedia PC Marketing Council and literally announced the multimedia computer at a flashy event at the American Museum of Natural History. During the early years of the PC market, IBM famously eschewed graphics and sound capabilities, treating them as if they were undesirable to business customers. But at a time when grunge music was first hitting mainstream radio, IBM was finally ready to sell the multimedia sizzle. So was Microsoft.

“Multimedia is the new industry. We have audio, video, sight and sound,” Bill Gates said, according to a UPI wire story, presumably as he attempted for something approaching showmanship. “When we look back, we’ll see our first efforts were inadequate.”

They were, of course, but man, did they move a lot of units. And a “unit” in those days was a whole bunch of giant boxes. The CRT was big. The CPU? Big. The accessories? Also big. Buying a computer in the early ’90s means something a lot different from buying a computer today. And being able to walk in a store and not have to worry about the whole package meant something.

(It meant so much that Microsoft actually trademarked the “Multimedia PC,” then gave the trademark away.)

Of course, multimedia, the concept, predated multimedia, the package deal, and was building into something. And traveling back in time to find the roots of the multimedia concept is sort of like watching the parts of a machine get fuzzier and fuzzier. “The simultaneous arrival of CD- ROM and electronic desktop publishing is a harbinger of the multimedia desktop workstation to come—the ultimate end-user communications and computing tool,” wrote Michael A. Conniff in a 1986 Computerworld article.

A 1984 New York Magazine article was even more bullish, and even fuzzier in end result. “I think this technology will open up incredible new avenues,” 3M project manager David Davies told the consumer magazine. “It allows you to combine all kinds of visual, audio, and textual information interactively. Now you can have arcade-quality laser-video games—like Dragon’s Lair—on your home computer.”

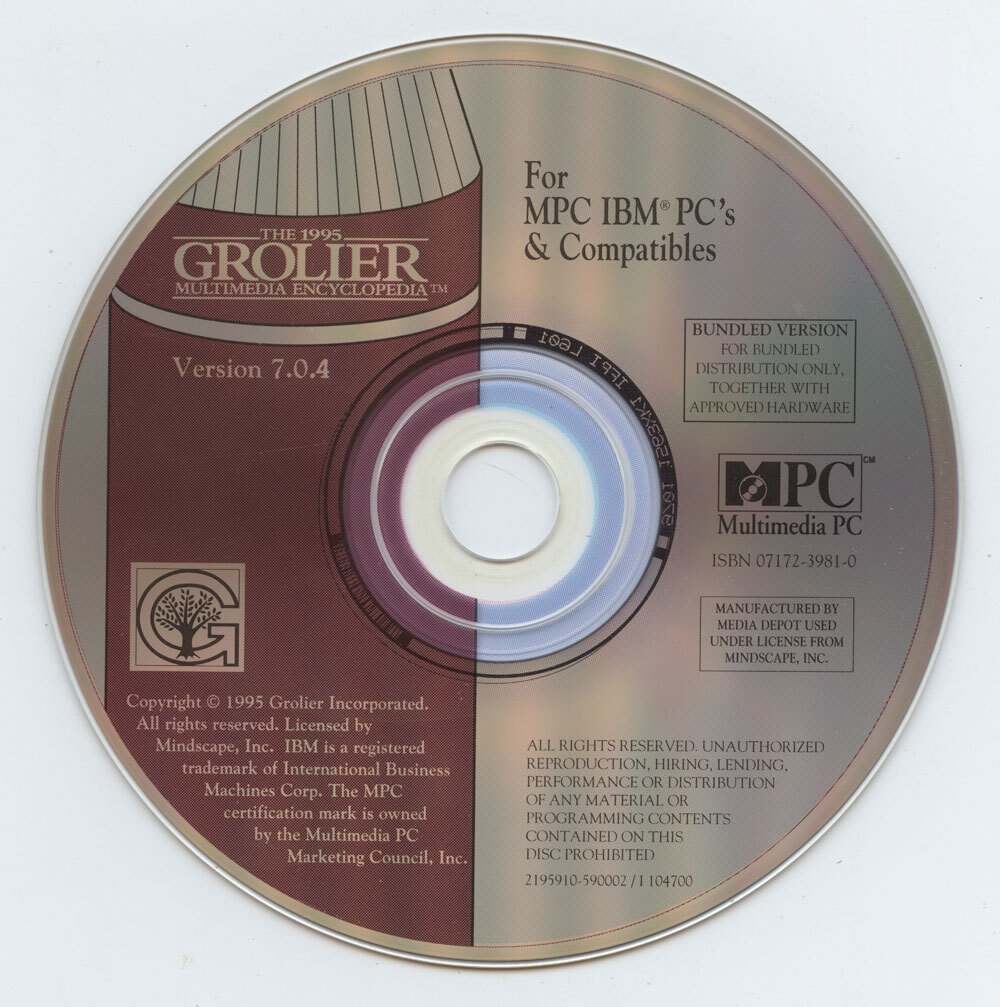

A 1995 edition of the Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia, prominently featuring the Multimedia PC (MPC) logo. (Internet Archive)

The challenge with multimedia PCs was not so much the selling of them as a broad concept—the CD-ROM was a cool enough idea that it kind of sold itself. Rather, it was the idea of baseline specifics, and what was good enough for the average user.

And that baseline meant that you were not only buying a computer, but a monitor, speakers, and a bundle of software that made it clear you were not wasting your money. It wasn’t just the box. It was the full package.

And in 1991, the Multimedia PC (MPC) standard made the full package an attainable goal for consumers. Pardon the pun, but it was a real Gateway drug.

2011

The year that Intel started to push the term “Ultrabook” to describe thin-and-light laptops along the lines of the MacBook Air—which, while a definite template for the concept, was not technically an ultrabook. While Ultrabook started as a copyrighted phrase that Intel used for computers that met its specifications, it became such a popular term that it came to define much of the laptop space over the past decade. It was a bit of a lifeline actually, as it came at a time when laptops were generally very chunky and easy-to-carry phones and tablets were starting to emerge. Less discussed is that the initiative is sort of an evolution of the same basic idea as the Multimedia PC—that is, a baseline standard for manufacturers to follow.

A training video for selling the Tandy Sensation, a multimedia PC from the early ’90s that was one of the final models the company sold. (It was concurrent with the Tandy Video Information System.)

The Multimedia PC standard was secretly an effort to rein in the clones after a decade of inconsistency

It’s long been said that the Commodore Amiga was ahead of its time, with many of the multimedia capabilities that it would take more than half a decade for the IBM PC to get in any reasonable way.

Likewise, the Apple Macintosh was a few steps ahead of the IBM PC on the multimedia front during its early years. And the reason likely has a lot to do with the clone market that berthed and represented the IBM PC’s strengths for years.

As early as 1986, companies looking to develop hardware and software for the IBM PC were looking for some form of standardization to help make the transition to the next generation somewhat of a lighter lift. An InfoWorld article from that year features a Microsoft official making the case for standardization around multimedia.

“Whenever there is a new technology, there is risk involved,” the firm’s Tom Lopez said. “Standards will help reduce that risk.”

(Funny aside: At the end of the InfoWorld article, there’s a comment about concern that CD-ROMs will become a “universal panacea” and replace human interaction. One of the people cited as making this claim was Philippe Kahn, the person often credited with inventing the cameraphone, a device that arguably was much more of a “universal panacea” than the CD-ROM ever was.)

It took a few years to get that standardization, and when it came, the word “multimedia” was right out front.

Even if it wasn’t “multimedia,” the PC industry needed something like this, because for the average consumer at the time, home computers were confusing because of all the choice. Remember, after all, that this is the industry that once sold magazines the size of phone books.

Compare buying a computer to buying a home video game console, for example. A Super NES purchased in 1995 may have some minor under-the-hood differences from a model produced in 1991, but both models are going to practically play Donkey Kong Country the same way. PC manufacturers, on the other hand, offered much more choice. Choice could be incredibly confusing, especially if, as many people were, they were buying their first home computer.

Plus, the lack of standards really created problems for the PC market as a whole, as tools like the Sound Blaster emerged out of sync with the larger movement. As PC Magazine stated in 1992:

Still, having the technology did not immediately create a general multimedia market for the PC platform. The components were designed individually and getting them to work together was a nightmare. User interfaces typically were not designed to take advantage of the multimedia hardware and the components were too expensive. Even more damaging, the lack of consistency among those various hardware products did not make it very profitable for software developers to bother creating multimedia applications.

The Mac and Amiga, by nature of being closed ecosystems, had an easier time with multimedia because all they needed to do was improve the baseline hardware across a few machines. The PC had to raise the standards for an entire industry of complex players. Hence, the need for MPC, which attempted to clear the air and ensure that consumers had something to go by.

Windows 3.0 with Multmedia Extensions, featuring the MPC logo. (via Nerdly Pleasures)

The Multimedia PC standard required frequent updates because of the continuing drumbeat of technology, and was aimed at making it clear what the required level of horsepower would be do do certain things. Those three levels, and their minimum hardware requirements:

- MPC1 (1991): A 386SX with at least 2 megabytes of RAM, a VGA display, a mouse, a 30-megabyte hard drive, an 8-bit sound card, and a single-speed CD-ROM. The intended target operating system was Windows 3.0 with multimedia extensions added.

- MPC2 (1993): A 486SX with at least 4 megabytes of RAM, a 3.5-inch floppy drive (not required in MPC1!), a display capable of 65,000 colors, a 160-megabyte heard drive, a 16-bit sound card, and a double-speed CD-ROM drive. The intended target operating system was Windows 3.1 with multimedia extensions added.

- MPC3 (1996): The equivalent of a 75-megahertz Pentium processor, 8 megabytes of RAM, a 540-megabyte hard drive, a PCI-driven graphics card capable of high quality graphics, support for MPEG1 video, and a CD-ROM drive capable of 4X speeds. The intended target operating system was Windows 3.11 or Windows 95. (This edition went out of its way to be less prescriptive about options to make room for competitors in the space, particularly in the processor department, where non-Intel competitors such as AMD were emerging.)

These results would get you different things from a quality standpoint. A 2016 video, put together by the YouTuber The Oldskool PC, showed the three levels of full-motion video playback based on MPC specs, using an old episode of The Computer Chronicles as a baseline:

By 1996, things had clearly improved significantly. We had conquered multimedia. At the same time, however, however, computing technology had advanced in such a way that prescriptive standards for what a computer should be no longer mattered as much for the consumer, even if one could argue that technology companies still needed them.

On top of that, computing experiences were incredibly diverse in nature. A desk jockey rocking Excel had different needs than someone playing Quake—and over time, those needs diverged beyond the level that a single broad recommendation could reasonably account for.

As a result, the Multimedia PC shaped what we used throughout the ’90s, but it did not live through the internet era.

“Let’s imagine MPC-HD has multiple levels, and when publishing your game, you can simply state that the minimum requirement is MPC-HD Level 1. That’s easy for developers to code for, easy for buyers to follow, and easy for manufacturers to advertise and profit from. One can only wish.”

— Bruno Ferreira, a writer for The Tech Report, making the case in 2012 that a modern equivalent to the Multimedia PC is needed for one specific audience—gamers. And yes, there’s probably a case for that, given that its competition, consoles, benefits from consistent baselines. But it has yet to happen. (Should it?)

The discussion of the Multimedia PC standard, and what a minimum system was supposed to look like, feels especially notable in the current moment, as Microsoft’s recent announcement of Windows 11 has put a spotlight on minimum requirements in the PC market.

Realistically, nearly any desktop computer from the past decade is enough for basic use cases. (Playing games or using high-end software, on the other hand …) But Microsoft aimed a lot higher than that, citing in part the need for an increased security baseline, also driven by a standard.

The problem was, the timing might have been a bit too soon, or the security standards a bit too cutting-edge, because the minimum requirements leaped up significantly with a single release cycle.

On the one hand, I think Microsoft is trying to do the same thing they always used to do with their software releases in the ’90s—create a technical baseline so that whenever people use their software, they’re running it on reasonably good hardware. But the problem is, reasonably good hardware is not really the problem anymore. In 1991, falling back two generations with your hardware was the difference between running Windows at a reasonable speed and not being able to run Windows at all. A 286 was a 16-bit processor; a 486 was a full 32-bit beast. (And we haven’t even brought up the CD-ROM and sound capabilities!)

These days, there are so many generations of Intel Core processors and AMD Ryzen chips and graphics cards with obscure numbers behind them, the problem is no longer ensuring the baseline. Everything is 64-bit and built around multiple processor cores. Nearly all of it can run, say, YouTube in a web browser at a reasonable speed. It’s really about keeping a massive breadth of machines working with the same individual pieces of software.

And perhaps, for that reason, Microsoft’s endeavor to raise system requirements in this way, even if for sound security reasons, may not play as well as it did in 1991. Outside of games and high-end professional software, many developers target their offerings at the browser, meaning that, at least from a consumer perspective, you can technically get by with the computing equivalent of a toaster.

We’re not in a world where we need a kingmaker to tell us to buy the hot new thing anymore. We know what we’re doing.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal! And thanks again to Setapp for sponsoring.