Hey all, Ernie here with a piece from Michael Bentley, who previously wrote for us last August to tell us all about quizbowl. Today, he hits us with a story what online gaming was like two decades ago, when the fans stepped in. Read on!

Today in Tedium: 2001 was a marquee year for video games. By the end of the year, the Game Boy Advance, GameCube, and Xbox had all launched. All-time classic games such as Metal Gear Solid 2 and Super Smash Bros. Melee were released. Many of these console titles offered great local multiplayer experiences. But save for a select few Dreamcast games, online gaming was limited to the PC. This provided an opening for a type of game we’re calling the online fan game. Today in Tedium, we look at three fan projects that brought online gaming, however imperfect, to some of the best titles of 2001. — Michael @ Tedium

The Prepared is a free newsletter that cares about manufacturing's cultural context

In this week’s issue: Bathroom walls full of used razor blades, information transparency in the global shipping industry, and seminal artworks of early 20th century industrialization. Subscribe for free here!

Today’s Tedium is sponsored by The Prepared.

The GameCube ASCII Keyboard Controller could only be used in Phantasy Star Online Episode I & II. Today it sells for $200 on eBay.

Controllers with full-sized keyboards: Where online gaming stood in the early 2000s

An endless topic of debate on gaming forums in the early 2000s was the relative merits of PC vs. console games. Although I was mainly in the console camp, there was no arguing that in 2001 PC gaming offered the superior online experience.

The only major console with online play at the time was Sega’s cult hit (and commercial failure), the Dreamcast. For US gamers, one of the highlights of the early part of 2001 was the Dreamcast’s most popular online title, Phantasy Star Online. A subset of those Dreamcast owners were playing over SegaNet, a dial-up ISP whose servers were co-located with the game servers to reduce latency. You also got a free Dreamcast keyboard for signing up. While this made chatting in PSO easier, the keyboard’s killer app was The Typing of the Dead, the best typing game of all time.

The PlayStation 2, launched to great fanfare in 2000 despite having a terrible slate of launch games, came without a built-in dial-up or ethernet port. North American gamers didn’t get an online adapter for two more years. The GameCube similarly required a separate modem accessory that was supported by even fewer games. And your only real multiplayer option on the Game Boy Advance was a link cable. A wireless adapter (only supporting local wifi play) wasn’t released until late in the system’s lifecycle.

Meanwhile, online PC gaming had been going strong for years. As early as 1984, Commodore 64 owners could sign up for PlayNET to compete against strangers in games like Chess and Go. Online gaming went more mainstream in the ’90s with popular first-person shooters such as Quake. Blizzard’s long-running Battle.net service was already powering Diablo and Starcraft.

By 2001, the PC scene also had a robust modding community. Like the projects we’ll discuss shortly, some of the popular mods of the era were developed to improve a game’s multiplayer. One of the most important mods in this category was Team Fortress. It expanded Quake’s online deathmatch, adding player classes and a greater focus on teamwork. The mod was popular enough to become its own standalone series.

Thus, the PC ecosystem was ready to fill in where console games were lacking.

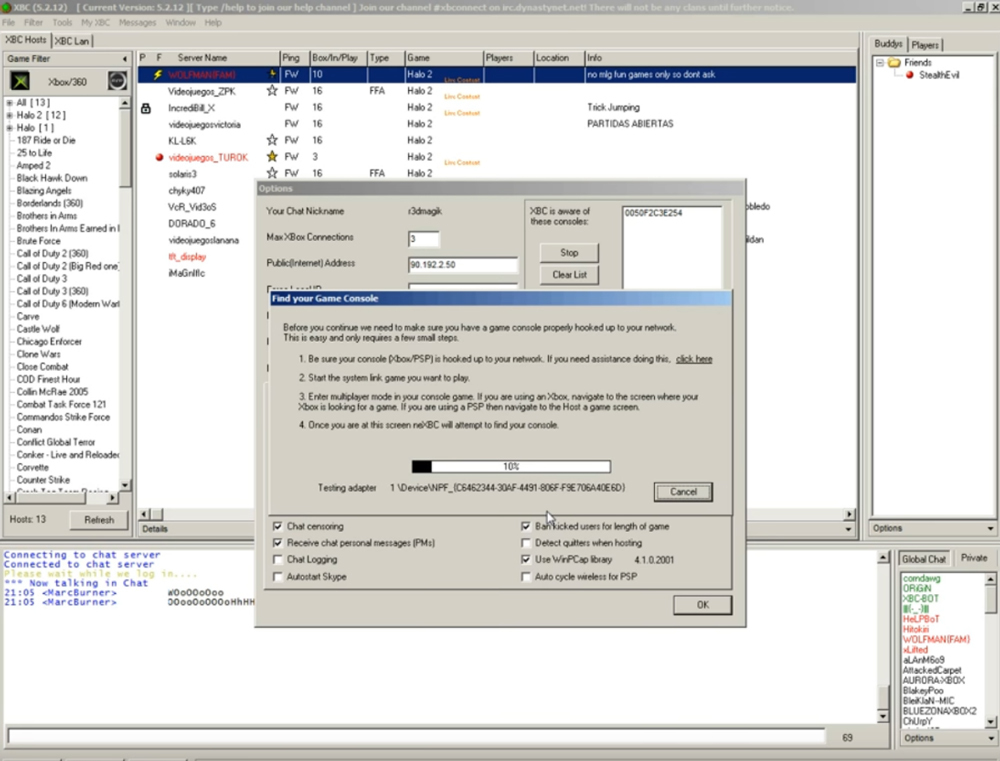

LAN multiplayer lobby in Halo: Combat Evolved. (Screengrab from Xbox Kai Fam)

XBConnect: Bringing your LAN party online

The Xbox, which also launched in 2001, was ahead of its competitors in online capabilities. Each console came with a built-in ethernet port and hard drive. While Xbox Live and online play wouldn’t launch until 2002, some Xbox launch titles supported multi-system play over LAN. So long as you were willing to haul Xboxes, TVs, controllers, games, and maybe a WRT54G router to one central location, you could play the Xbox’s killer app, Halo, with up to 16 people.

Schlepping all that equipment was no obstacle for my friend group. We spent practically every weekend in my basement playing Halo LAN matches. We thought we were good enough that we were going to dominate a Halo tournament at our local gaming café. Instead, we got crushed by a short-handed team of 12-year-olds who honed their skills on XBConnect.

XBConnect was an app that made your PC look like other Xboxes (or, later, Xbox 360s and PSPs) on a LAN connection. Like a VPN, it tunneled packets intended for one use (direct LAN connections) for another purpose over the internet. This site breaks down network tunneling in more detail.

XBConnect Version 5.2.12 attempting to connect to a console. (Screen grab from TeamInfusedTV)

XBConnect wasn’t exactly a plug-and-play experience. Numerous YouTube videos (posted after XBConnect’s early-2000s heyday) go through the multi-step process to get the PC drivers and router settings needed to make the app work.

Even on a broadband connection, XBConnect struggled to provide smooth connections. Halo’s netcode, such as it was, made assumptions about latency and connectivity on a local network that don’t hold up when played online. Many XBConnect Halo sessions stalled out with long delays for the player who was not the host. (You can witness some of the lag in Halo 2 at minute 2:20 in this poorly captured video.)

But given a lack of alternatives, the XBConnect Halo scene flourished. Making a Halo clone was well beyond the capabilities of independent developers at the time. This was not the case for games on a contemporary portable system.

six

The number of games in Nintendo’s Famicom Wars series exclusive to Japan before Advance Wars was released in the West. Advance Wars itself didn’t get a Japanese release until three years after the US release. And Japanese fans were only ever given a digital release of Days of Ruin, the final game in the series.

Advance Wars: Like Fire Emblem, but with unit building and no permanent characters (source)

Filing the serial numbers off Advance Wars

In the fanfiction community, the phrase “filing the serial numbers off” refers to severing the links between a fan work and the copyrighted original. This process almost certainly happened for our next game, the Advance Wars fan game Battalion: Head-2-Head.

Advance Wars on the Game Boy Advance was the first turn-based strategy game that really clicked with me. There was something innately satisfying about building units, capturing enemy territory, and exploiting the game’s somewhat suspect AI to finish maps with the highest ranking.

The series originated on the NES as Famicom Wars but didn’t receive a Western release until Advance Wars hit the GBA on the soon to be infamous date of September 11, 2001. (Wikipedia claims Monday, September 10 as the release date, but most games in this era were released on Tuesdays.)

I was in high school at the time, which was an ideal time to get into the game. Advance Wars had a lengthy single player campaign, but the real challenge was in multiplayer. Thanks to its turn-based nature, you could pass a single GBA around in class without needing additional systems or copies of the game. I spent many a study hall in such battles.

Of course, local multiplayer has its limitations. Once you get tired of playing your friends, what’s left to do? You turn to the online fan game.

Dedicated Advance Wars fans may expect me to talk about Advance Wars by Web here. That site’s still going strong after 15 years. It offers a web-based Advance Wars experience using graphics and gameplay mechanics from the Nintendo originals.

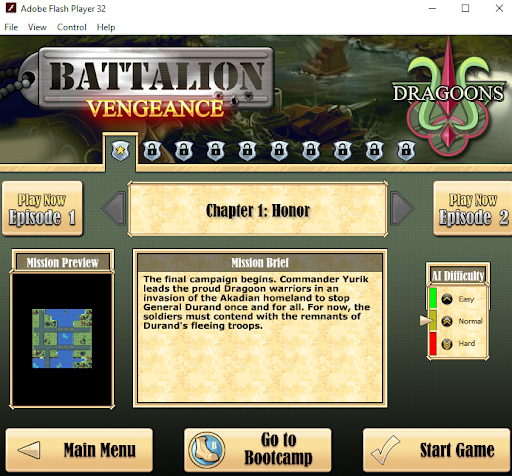

But I’d like to discuss an earlier title, Battalion: Head-2-Head. This was an online Flash game heavily inspired by Advance Wars by a developer who went by the name Urbansquall. Confusingly, it’s unrelated to the later Battalion Wars games officially released by Nintendo on the GameCube.

A match in Battalion: Head-2-Head. (source)

As you can see from these unit screenshots, the game more than a little borrowed from Advance Wars in its aesthetics and gameplay. (In a 2005 interview, Uransquall claims the game originated as an experiment in making a massively multiplayer online space shooter in Flash. Even if that is the case, the final product was highly derivative.)

The game wasn’t an exact copy. Subtle differences in how HP and tile defenses worked affected high-level play. The game didn’t include Advance War’s signature (and unbalanced) CO Powers, making match outcomes more determined by skill. But anyone familiar with Advance Wars could dive right in.

And unlike the GBA entries, Battalion Head-2-Head had online multiplayer play—in fact, it didn’t even have an option to play against the CPU in its early days.

Battalion: Vengeance running today via the Flashpoint Launcher

Though the game was never as popular as Nintendo’s entries, Battalion Head-2-Head had an active community for several years. I got so into it one summer that I even successfully lobbied for the addition of a new flame-throwing infantry unit. More importantly, the game satisfied my desire for a competitive Advance Wars experience when Nintendo wasn’t meeting that need.

Battalion: Head-2-Head’s server went offline around 2009. According to this surprisingly detailed Kongregate Wiki page, in its later years the series was put onto Kongregate and got several stand-alone single player entries that diverged more from the Advance Wars original. Luckily, those games have been preserved from the great Flash shutdown through BlueMaxima’s Flashpoint preservation project.

A screenshot from Golden Sun’s notoriously plodding intro. I hope you weren’t planning on moving on your own for the first hour.

How my cheesy Golden Sun fan game built a small online community

Finally, I want to discuss an online fan game that borrowed unashamedly from the source material. And in this case, the fan doing the borrowing was me.

Golden Sun was an RPG by Camelot that appeared on the GBA a month before Advance Wars. It was one of the first must-have original games for a system whose launch titles largely consisted of updates and remakes of SNES titles. I was particularly drawn to its innovations over the traditional JRPG format. Special moves called Psynergy added Zelda-like puzzle solving elements to the overworld. The Djinn system added strategy to battles beyond the “press A to grind” mechanics common in 16-bit JRPGs.

I came to making a fan game for Golden Sun after first writing an FAQ for it. This FAQ expanded into a website called Golden Sun Anonymous. Countless threads on the site’s forums were devoted to Golden Sun’s much-anticipated sequel, the Lost Age (the original game notably ends on a cliffhanger). The Golden Sun community was eager for more content.

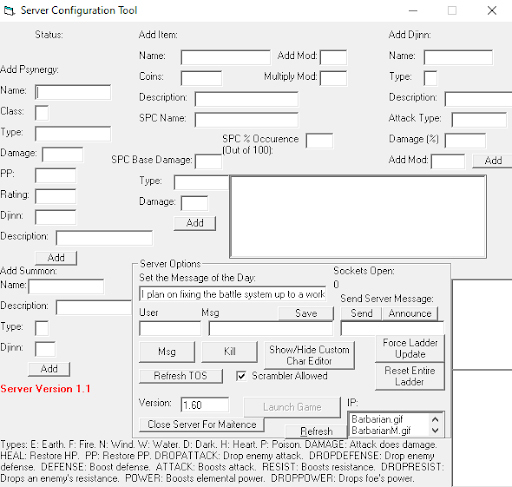

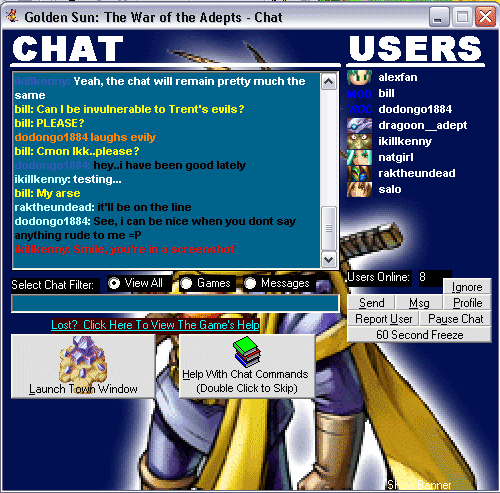

I tried to remedy this by developing my own take on the game. Building on some earlier games I had created in Visual Basic, I read up on the basics of making online games at PlanetSourceCode (the Github of its day, now literally on Github). Despite an extremely naïve architecture, I was able to build a server running on my home dial-up connection that could handle about 50 players online at a time.

The server interface. Simple, right?

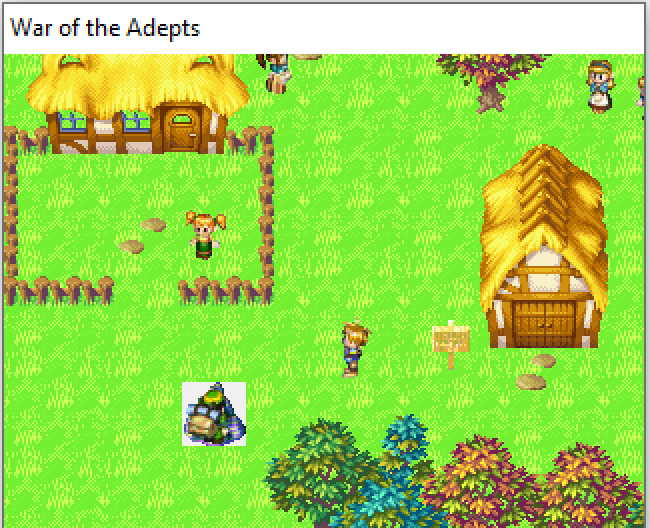

Golden Sun: The War of the Adepts (WOTA), as the game was called, takes its title from “adepts,” Golden Sun’s term for characters that had the ability to use Psynergy. At its core, WOTA was an attempt to translate the link-cable multiplayer battles in the GBA original to online combat.

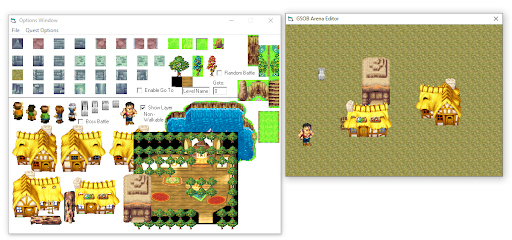

WOTA’s barebones single player, where players could earn coins to improve their multiplayer character. You may have noticed a non-canon character in this.

Admittedly, the battle system in WOTA was simplified and clunkier than in Golden Sun. Golden Sun’s four-on-four battles were reduced to one-on-one melees. Lacking documents like this in-depth battle mechanics guide matches were considerably less strategic.

That’s not to say there were no improvements over the original. For instance, before each WOTA battle, players would race in an obstacle course inspired by some of the log-rolling puzzles in Golden Sun’s overworld. The winner would get a stat boost and the right to attack first in the battle.

The level editor for creating obstacle courses and overworld maps in War of the Adepts.

But even a crude implementation of Golden Sun was enough to attract a bigger fanbase than I had ever thought possible. What WOTA lacked in graphical fidelity and in-depth battling it made up for in community and customization.

Most of this community developed in the game’s two chat options: a conventional IRC-like chatroom, and a world map where text appeared above your player character. The latter isn’t all that different from place-based chat services such as Cozy Room, popular in this era of Zoom fatigue.

The IRC-like chat interface of War of the Adepts.

One of the most popular features of the game had little to do with Golden Sun itself. Each week, I hosted Scrambler sessions for a chance to win a custom avatar. Scrambler is a simple word game where you’re given a category and a scrambled word. The first person to type in the unscrambled word wins. For instance, “palep” in the category of “fruit” would unscramble to “apple.” I stole this idea from bots popular in AOL chats in the 1990s. Learn more at this Tripod site.

Over time, as with many online communities, the original reason that people connected with WOTA started to fade. Battles became less common. Instead, the chat became a place where people connected with friends and discussed their life—much like any Discord community today.

I had visions of making a sequel to the game that was much more faithful to the original. But like many fan projects, my interest eventually fizzled out and it never expanded beyond a demo stage. I also never could figure out exactly how Camelot generated cliffs from the underlying tile aspects. (And still can’t! Send me an email if you know the secret.)

Screenshot from the unreleased sequel to War of the Adepts. It’s much closer to the aesthetics of the original GBA game.

The game never got so popular that it attracted the attention of notoriously litigious Nintendo. Instead, I voluntarily took the server offline on June 5, 2004, which I think is the date that I graduated high school.

26

The number of days between when Microsoft shutdown the servers for the original Xbox Live in 2010 and when the final player, Apache N4SIR, disconnected from a Halo 2 match. According to Kotaku, Microsoft offered the last few Xbox Live diehards beta codes for Halo: Reach to lure them off the service.

These days, online multiplayer is no longer the exception for console games. Even on Nintendo systems, it’s usually included by default. (At least for a few years; RIP Super Mario Maker on the Wii U) But this doesn’t mean the hobbyist multiplayer experience has completely gone away.

XBConnect itself became newly relevant after Microsoft shut down Xbox Live for the original Xbox in 2010. Suddenly, there was no way to play online Halo 2. But as with most things on the internet, the closed-source XBConnect itself shut down three years later. (An XBConnect 2.0 announced in a YouTube video in 2017 was never seemingly completed.) Those hankering for an online Halo experience instead should turn to the similar XLink Kai service, as documented in this Modern Vintage Gamer video.

Fans generally don’t need to re-create their favorite games to play them online. But there are still many cases where unofficial games step in to fill a void left by a series’ official caretakers.

Sometimes official properties lay dormant. This is the case with Advance Wars. There hasn’t been a new game in the series since Days of Ruin on the DS. Intelligent Systems, the developers behind the series, have spent the last decade working on their more successful series, Fire Emblem and Paper Mario. As a result, the best “Advance Wars” game of the 2010s is WarGroove, Chucklefish’s excellent spin on the series. Pick it up for your Switch.

In other cases, a property may be getting new games but they’re not up to fan standards. Perhaps no series embodies this more than Sonic. For much of the 2000s, Sega released a stream of mostly terrible 3D Sonic titles. I personally liked Sonic’s 2D entries on the GBA and DS, but hardcore Sonic stans did not feel they measured up to the series’ Genesis glory days.

The series was revived by a group of ROM hackers, among them Christian “Taxman” Whitehead, whose iOS “Retro Engine” was so good he was hired by Sega to code official Sonic iPhone ports. Whitehead and others would then be tapped to release the series’ 2D comeback, Sonic Mania.

Finally, a whole new class of games has emerged in the last decade or so that channels the creative energies of fans directly into the gaming experience. No game exemplifies this more than Roblox, a Minecraft-esque platform that promises today’s youth the potential to earn “millions” creating pizza shop simulators or IP-stealing Avengers games if they hit it big. When someone makes the next Golden Sun sequel, maybe I’ll sign up.

Online gaming affinity communities of the kind that once connected via webrings, forums, or fan games are now sought out for monetization by publishers. A whole genre of Minecraft-like games is built on channeling the creative energy of their players. Perhaps none more so than Roblox, which openly advertises its potential to earn creators “millions” in “serious cash”. As Alexi Alario argues in Real Life Magazine, “the user’s creative labor is built in as an expectation.”

Now, as then, the hard work is the fun part.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal!

And thanks again to The Prepared (a great newsletter) for sponsoring. Be sure to give them a look!