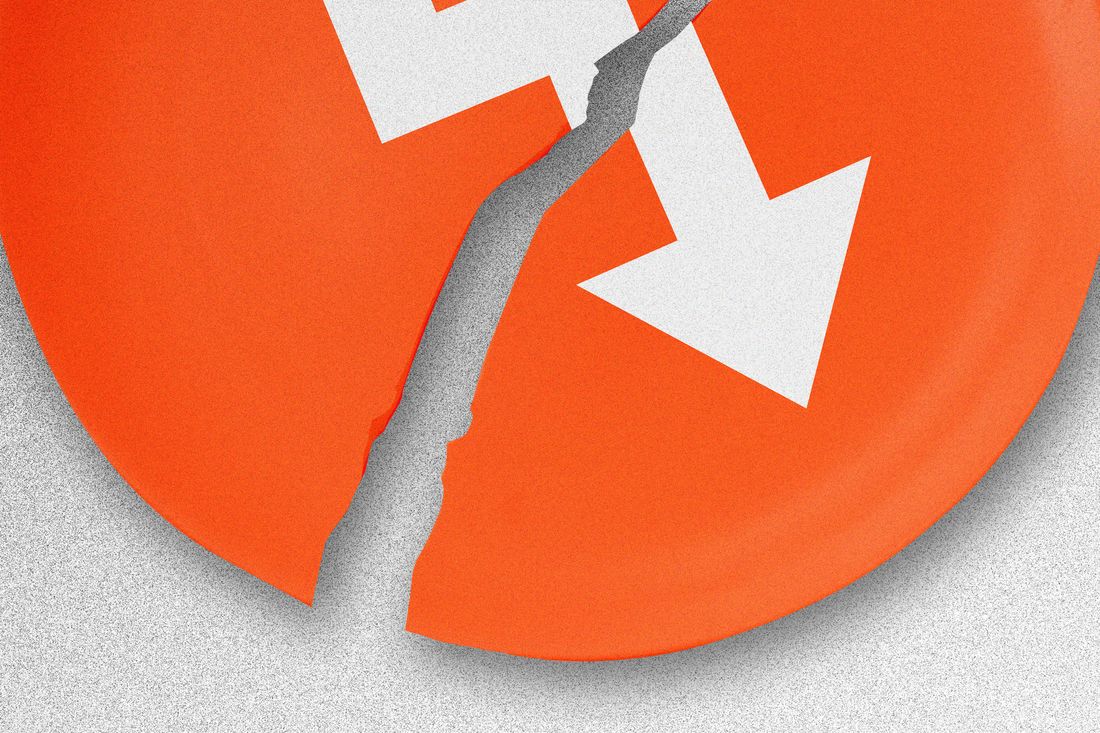

Earlier this month, the staggeringly bad market performance of BuzzFeed managed to get even worse. Shares of the media company fell more than 40 percent on June 6, just days after the expiration of a lockup preventing company insiders from selling their stock.

BuzzFeed is now trading at just $1.68 — a decline of nearly 85 percent since the moment it went public on December 6 by merging with a special-purpose acquisition company, or SPAC. It’s a startlingly poor return even by the low standards of SPACs, which have recently crashed en masse. Other media companies that had been planning similar maneuvers, from Vice to Forbes to Bustle, have abandoned their plans. Under pressure to be more profitable, the award-winning BuzzFeed newsroom — it won a 2021 Pulitzer Prize for reporting on mass detention camps in China — is shrinking via layoffs and buyouts.

One continuing pall over the company is a lawsuit filed by 91 former (and certain current) employees, who alleged in March that BuzzFeed had botched its public offering and prevented them from selling shares worth millions. BuzzFeed countersued in April, seeking to move the case out of arbitration and into Delaware chancery court. As the litigation played out, I talked to current and former executives and employees and found a dynamic that may be among the most toxic in all of digital media. “I’ve never seen morale worse there,” says a former reporter. One group of ex-employees, it turns out, was able to sell shares relatively easily after the SPAC deal. This subset apparently includes former editor in chief Ben Smith, who held on to his stock options for most of his tenure as media columnist at the New York Times but sold them before announcing his departure from the paper at the beginning of January. (Smith declined to comment.)

The trading difficulties experienced by some former employees come down to an issue of converting stock from one class of shares to another and whether the company gave them adequate time and notice to execute the switch. Who knew what, and when, could turn out to be expensive for BuzzFeed. Says a former executive who was part of the contingent that was able to sell, “The people I was talking to knew that was going to be a nightmare in the weeks before.”

Hannah Anderson was in her obstetrician’s office early on December 6, the day the stock she had received as part of her compensation package at BuzzFeed was finally going to be worth something. Nearly eight months pregnant with her second child, she was only half listening to the doctor, instead thinking of ways she would celebrate. “I was literally refreshing the CNBC web page while the doctor was going over the signs of labor with me,” she says. Anderson’s husband had taken the day off to stay in front of the computer and trade when the time came. They had calculated that the proceeds of the BuzzFeed SPAC would be enough to pay for college for both their kids. “We were so excited,” she says. “And then it just all came crashing down.”

SPACs, an alternative to traditional IPOs, became trendy during the market frenzy of the pandemic era. In the title of a press release issued before the listing, BuzzFeed boasted that it would be the “First Publicly Traded Digital Media Company.” (Vox Media, which owns New York Magazine, was rumored to be exploring a SPAC maneuver in 2021. After a merger this year, Vox Media also owns Group Nine SPAC LLC, the sponsor of the Group Nine Acquisition Corp SPAC.) Executives prided themselves on being in the vanguard of a new financial model for the industry; for years, they had dangled stock options as compensation for high- and low-ranking employees alike.

Anderson, who wrote sponsored content for BuzzFeed for four years until 2015, was one of dozens of former employees who planned to sell their stock at the earliest possible moment. But on the big day, to her and her husband’s horror, the shares weren’t available to trade in their brokerage account. By the time they were, the stock had fallen at least 60 percent from its first-day high.

The group now suing BuzzFeed includes staffers who started at the company in its early years, from reporters who covered politics to those who wrote quizzes or helped build the website. They remember an era of perks like free pizza and beer on Thursdays and frequent celebrity sightings in the office, which gave a heady sense that BuzzFeed was on a trajectory just like its logo, an arrow climbing skyward. Some were making as little as $35,000 a year, but the pay was augmented by stock options they purchased when they left the company, borrowing money from their parents, their significant others, or a bank.

One former staffer took a pay cut and a less prestigious title simply to join BuzzFeed. She told me, “I remember talking to HR and saying, ‘Is there any wiggle room in the salary?’ And they were like, ‘Absolutely not, but think of all the benefits,’ and they talked about the stock. There was always the hope that this could be a huge payout at some point.”

Over the years, the idea of a big payoff languished as BuzzFeed raised more venture capital and pushed an IPO farther down the road. But in the middle of 2021, when BuzzFeed announced its intentions to go public via SPAC, it renewed many workers’ dreams of a liquidity event. Those people, having started at BuzzFeed as much as a decade ago, were now in a different phase of life, with spouses, children, and mortgages. All SPAC stocks start out trading at $10, and the employees mentally added a zero to their number of shares, fueling visions of paying down student loans or buying a house. Based on that price, ex-employees held shares worth anywhere from several thousand dollars to as much as $1 million.

BuzzFeed was scheduled to debut in early December, but not until a couple of days before Thanksgiving, at 5:38 p.m., did the company begin informing its former-employee stockholders of the process by which they would be able to trade. In that email, signed by “the Stock Admin Team,” the company also delivered the news that after the merger, the ex-staffers would receive only a fraction — less than one-third — of the shares they had previously held. But the steps seemed straightforward enough, essentially involving setting up a new account to hold the stocks with a company called Continental and then moving them to a brokerage. The way BuzzFeed described it, much of the process would be automated. The top of the email read, in bold, “At this moment in time you don’t have to do anything.”

Over the following days, the former employees received a flurry of documents to print, sign, and return, but as the date of the SPAC deal approached, they still did not have their shares in hand. Some were running into problems setting up their accounts with Continental. BuzzFeed had apparently sent their login credentials to their old @buzzfeed.com addresses, despite the employees having previously confirmed their new contact info with the company. Others found that even after following all the instructions, their shares did not turn up, and they could not get an answer from anyone at Continental or BuzzFeed. Emails to the “stock admin team” went unreturned. Some even tried emailing hello@buzzfeed.com, to no avail. Many turned to a Facebook group for ex-staffers called Buxxfeed. “It was like a madhouse of us just grasping at straws,” says Anderson.

One special feature of SPACs is that they allow initial investors to cash out their shares at $10 before a merger goes through. With BuzzFeed, 94 percent of eligible investors redeemed their shares — one of the highest redemption rates of all SPACs that went public last year, according to SPACInsider, which tracks those deals. “I definitely felt a sense of impending doom about that,” says someone who worked as a reporter at BuzzFeed in its early days. That feeling would intensify. When the stock began trading under the ticker BZFD, the group of former employees, with no access to their shares, could only watch as the price briefly rose to above $14 and then began to fall.

As the ex-staffers groused to one another, trying to figure out if anyone had been able to trade, it became clear that a certain contingent of their colleagues was more fortunate. This group consisted of those who had left the company relatively recently and still held unexpired options as opposed to stock — a cohort that seemed to include Smith. They had a vastly different experience in the days before and after the SPAC deal. “It was supersmooth for me,” says one former staffer who left in 2019 and sold on the first day of trading, adding that she received prompt responses each time she emailed a question to the stock-admin team.

As they stewed, the former employees who were unable to sell tried to solve the mystery of what had gone wrong. The answer didn’t appear until after BuzzFeed stock was trading publicly for two days. It turned out the workers had needed to take a crucial step, though none of the emails from BuzzFeed and Continental in the days leading up to the offering had mentioned it. A quirk in BuzzFeed’s history meant former employees held a class of shares with 50 times the votes of the shares that would trade on the exchange — an artifact of the company’s early days when management wanted to make sure investors didn’t end up with too much power. As BuzzFeed prepared to go public, this presented a problem since its executives needed to consolidate voting power among the leaders of the company. In order to sell their stock, the ex-employee stockholders would need to exchange their high-voting Class B shares for single-vote Class A shares.

At 6:23 p.m. on December 7, the company’s stock-admin team emailed again: “For context, only yesterday did we learn that holders of Class B shares would have to take additional steps to convert their shares to Class A, before they could be transferred for sale.” That paperwork was likely to take several days more to process, the email continued, expressing regret that Continental had not included that information earlier. “We understand and sympathize with your frustration with this process,” it said.

The explanation was strange for several reasons. First, one of the former employees had received a message last July from a BuzzFeed lawyer that included a document to sign to convert the shares — seeming to suggest the company had been aware of the requirement much earlier. The email referenced a conversation with Jonah Peretti, BuzzFeed’s CEO, and went on to say, “Please note that Class A common stock are the shares that are anticipated to be publicly listed.” Yet even the person who received the instructions early was ultimately unable to trade; they have since joined the lawsuit.

Of all the things in a SPAC listing to mess up, securities lawyers say, this was unusual. SPACs aren’t short on complicated procedures, but this isn’t one of them. “It is not hard to do. It’s not hard to see that these people are going to have to convert, and it’s not hard to send a letter,” says Michael Klausner, a Stanford law professor who oversees a database of securities class actions including SPAC litigation. “I don’t see an explanation, and I can understand why the employees would be suspicious that this was done on purpose.”

Yonaton Aronoff, an attorney at Harris St. Laurent & Wechsler who is part of the team representing the employees, says the alleged errors are so odd he has never seen another case like it: “It seems pretty unique in the amount of negligence, at least, that was built into the process, and dysfunction.”

In a statement, a BuzzFeed spokesperson said the company was “confident that we will prevail in any action on this issue.” A person familiar with BuzzFeed’s SPAC process says it offered training sessions to current employees and didn’t believe it was obligated to instruct former workers on how to handle their equity — that the responsibility fell to Continental. Executives also worried that telling ex-employees to convert their shares, and therefore cede voting power back to BuzzFeed, could somehow risk a securities violation. (Finance lawyers I spoke to said this sounded unlikely.)

Continental, for its part, told Axios in December that it was “sensitive to the shareholders’ inability to sell before the share price sank,” but it blamed the issues on the “timing of the records” and “directions” it had received from BuzzFeed and its lawyers.

“It all felt very rushed and unprofessional in a way because of the speed at which things were being requested of us,” says a second former executive who is part of the lawsuit. “It’s such a big oversight that I can only think, Was there something else going on behind the scenes? It’s shocking.”

One major reason BuzzFeed forged ahead with the SPAC is that it wanted to acquire Complex Networks. BuzzFeed had agreed to purchase the entertainment company with $200 million in cash and $100 million in stock and could close the deal only if it went public. A traditional IPO would have taken longer. “The timing would have meant we would have lost that deal,” says the person familiar with BuzzFeed’s SPAC. “We would have had to walk away from Complex if we were like, ‘Let’s pause and think about letting the market improve.’”

Some people involved in the listing argue that going public was the best option for the employees. Even if their shares are worth little at the moment, it’s still more than nothing — which was all they had in hand when BuzzFeed was private. “I don’t really see the employees as victims here,” says a former executive. “If you said to me, ‘Would you rather have shares at $4 or have shares that you could not sell maybe ever?,’ I think most people probably would have taken that deal. I don’t think there’s a deep issue of justice at play here. Justice for people who made $50,000 instead of $100,000? Come on.” Besides, the person adds, it’s foolish for anyone to put faith in a SPAC, a Wall Street invention that has birthed its fair share of scams: “You’re the person participating in the heist. Ultimately, you can’t really turn around and complain that your share of the takings wasn’t what you thought it should be.”

Another part of the problem is that seemingly all of BuzzFeed’s former employees had the same intention when the stock began trading. “My plan was to dump it all, day of,” says one. All the others I spoke with said the same. That meant their alleged losses — or what they believe they could have pocketed — are likely not quite what they appear to be, say market analysts, because very few could have sold at the peak. When BuzzFeed went public, only a relatively small portion of shares was available to trade (an amount known as the “float”), meaning that the price spiraled down quickly as soon as anyone really began selling. Executives like Peretti and other company insiders were legally barred from trading for six months. (Peretti has not sold any of his shares, according to BuzzFeed’s public filings.)

That’s little comfort to the former staffers who feel they were at least entitled to a shot at timing the market. “This mattered to people who didn’t matter to BuzzFeed,” says Aronoff. He says the company has shown “zero interest” in discussing a settlement.

BuzzFeed’s decision to sue its former employees seems only to have angered them further. “It felt like them punching down a little bit, showing me that they don’t give a shit,” says Anderson. “I feel like we were conned.”